Back in late 2024, I started taking daily village walks in Langkawi as a healthier lifestyle goal. It’s easy to do, free and all it requires of me is stepping out the door and just doing it. By taking the smaller village side roads I’m able avoid busy road traffic and kind of get lost in my own thoughts. But along the way, I’ve also observed a lot of nature and day-to-day life in various kampungs (villages).

What I’ve learned is that beyond Langkawi’s beaches, resorts, and geoforest parks lies a quieter world of traditional Malay kampungs. The surrounding greenery in these villages is full of fascinating plants; some used for food, others for medicine, and many with cultural significance. These kampung plants aren’t just background scenery; they’re a living part of Langkawi’s heritage.

It was the humble ulam raja that enlightened me to the intriguing complexities of kampung horticulture. During one of my morning walks, I saw a man picking seeds from tiny flowers in his yard and I couldn’t resist being nosy.

He was kind enough to introduce me to the ulam raja, a plant I had previously thought was a mere roadside weed. As I looked around, I realized that my preconceived notion of a few unkempt kampung yards here and there was actually wrong. They were wonderlands of heritage, and I was surrounded by extensive community household gardens that went far beyond a few decorative potted plants. Some were so extensive they were growing wild, fair game for any passerby neighbor.

The Magic of Langkawi’s Kampung Horticulture

Unlike the more designer-style ‘traditional kampung’ accommodations popping up around Langkawi, curated and aimed at luxury-minded visitors, true kampung horticulture is a fascinating mix of the random, the planned, and the decorative. Seamlessly balancing aesthetics with practicality. Which to me, is nothing short of brilliant.

Langkawi’s kampung roads aren’t just charmingly old school; they’re fascinating. The various roads are often lined with useful, edible, and sometimes surprising plants. Some you may know and others are waiting to be discovered. Whether you’re a curious vacationer, a heritage fan, or a local reconnecting with nature, here’s a small sample of plants you might come across during a village walk in Langkawi. Trust me, there are plenty more, but for now here are 20 to get you inspired to take a kampung walkabout.

Keladi Asam/ Wild Taro/ Colocasia gigantea

Garden fresh takes on new meaning in Langkawi! Imagine my surprise to see a local woman collecting (what looked to me as ‘elephant ear’ plants). After several failed Google searches for more information, I went back to that household and got the dirt (so to speak). Come to find out that this is a keladi plant (wild or sour taro), but not just any old keladi plant. This is keladi asam, and the stalks (batang) are used in cooking namesake dish Keladi Asam, a coconut-based tamarind curry and other sour and spicy local dishes such as Asam Rebus or Masak Lemak.

Keladi asam is a type of wild or semi-cultivated taro plant commonly found in Malaysia. The plant is valued not only for its flavor but also for its ability to grow easily in home gardens or damp environments such as riverbanks, paddy fields, and even ditches. Fair warning though, keladi asam is usually soaked and boiled before use, to remove calcium oxalate crystals, that can cause skin itching or irritations. Perhaps not a plant a novice really wants to mess with. Correct identification alone could be challenging, but you can try!

Although this plant is usually used as food, some parts of the plants are included in traditional herbal practices for natural detoxification and anti-inflammatory remedies. The keladi asam is also believed, by some, to ward off negative energy when planted near the home. That alone makes it a keeper in my book.

Pokok Belimbing Buluh/ Bamboo Starfruit/ Averrhoa bilimbi

Pokok belimbing buluh (aka bamboo starfruit) is a hearty local tree which is easily recognized by its fruit. The fruit looks like tiny pale cucumbers (or fingers) growing straight from the tree trunk. It’s odd-looking indeed.

The fruit is quite sour and is a popular ingredient in traditional dishes such as Sambal Hitam, Asam Pedas and Bilimbi Pickles. In addition to its culinary uses, belimbing buluh is also used as a traditional medicine. Its medicinal properties are believed to help treat ailments like high blood pressure, coughs, and fevers.

However, due to its high acidity, belimbing buluh should be used in moderation. Over-consumption (especially of the raw juice) could irritate one’s stomach lining or adversely affect the kidneys in folks with pre-existing conditions. Belimbing fruit is also rich in oxalic acid, a naturally occurring compound that contributes to its sour taste. In large amounts, oxalic acid can interfere with the body’s ability to absorb minerals like calcium and, in some cases, may contribute to the formation of kidney stones.

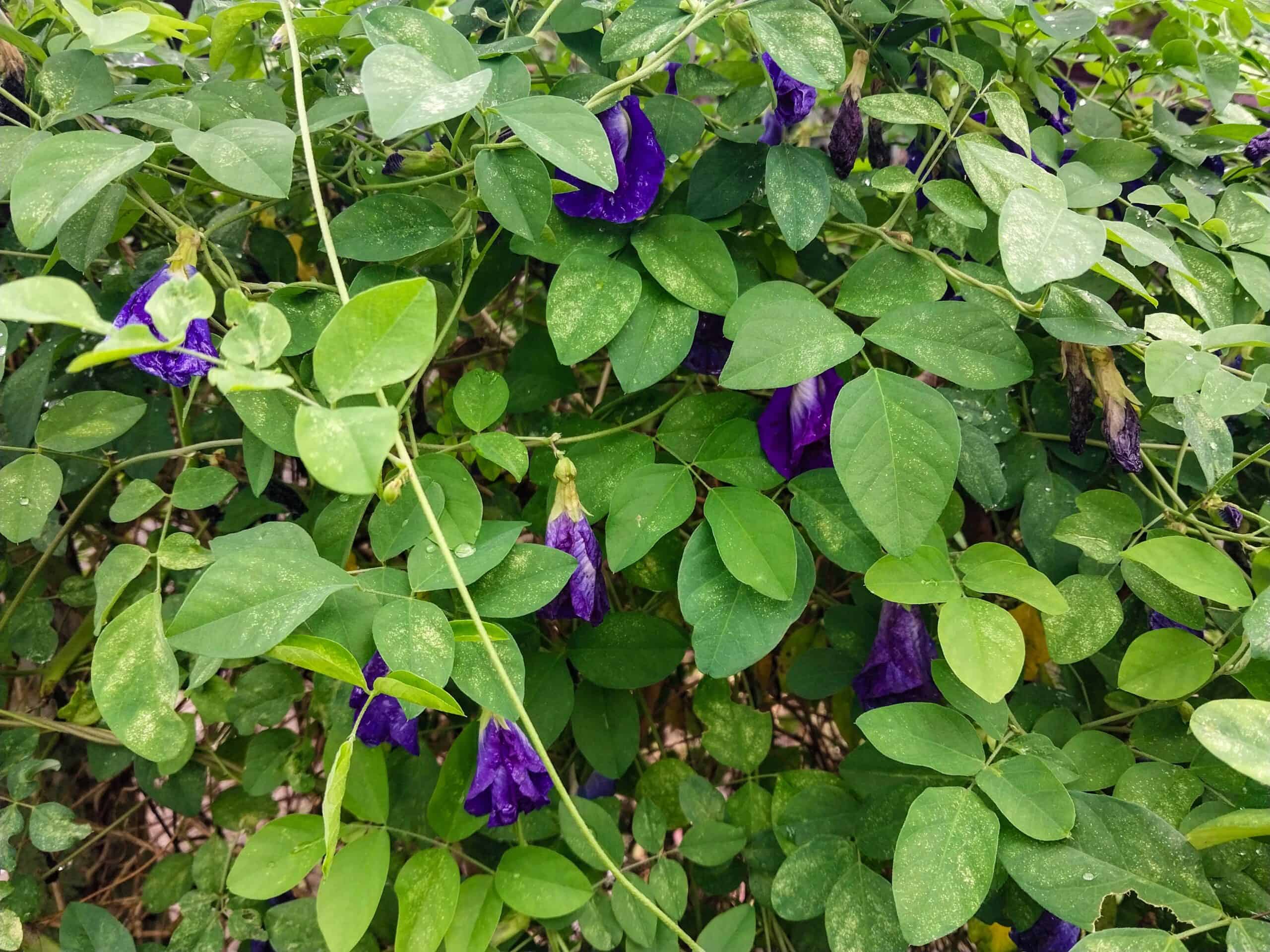

Bunga Telang/ Butterfly Pea Flower/ Clitoria ternatea

This little beauty is the bunga telang (butterfly pea flower (or butterfly blue pea flower). You’ll usually find it tucked away in a tangle of green vines, but I’ve come to know it as a tiny burst of color with many interesting uses.

In Langkawi, it’s commonly used as a natural food coloring for Nasi Kerabu (that famously blue rice) and also brewed into Butterfly Pea Tea. When the flowers are steeped in hot water, they release blue pigments called anthocyanins. These pigments are pH-sensitive, meaning they change color depending on what they’re mixed with. Add something acidic like lemon or lime juice, and the blue turns purple. Mix in something alkaline (like baking soda), and it shifts to green or teal. How cool is that?

I also recently learned that bunga telang is not only beautiful, it’s been used in traditional medicine for generations. Packed with antioxidants, it’s believed to help balance blood sugar and even support weight management (when used in moderation). Traditional healers have turned to it for everything from calming the mind and easing anxiety to boosting memory and regulating menstrual cycles. Pretty amazing for such a small flower, right?

Pokok Kelapa/ Coconut Palm/ Cocos nucifera

The pokok kelapa is a headliner of kampung life and with good reason. Should you ever find yourself stranded on a tropical island, whether in Malaysia or elsewhere, the multi-purpose pokok kelapa (coconut palm) could be your greatest survival asset. This palm grows quickly and produces coconuts year-round. But this tree goes beyond just gifting the planet with coconuts (kelapa), the entire tree is creatively usable.

From making palm frond roofing material and broom bristles to various decorative items, musical instruments and kitchen utensils, the list of its uses is lengthy indeed. It also plays a big role in local Langkawi cuisine, where coconut milk (santan), grated coconut (kelapa parut), and even coconut oil (minyak kelapa) are essential ingredients in many local dishes, from rich curries and kuih to nasi lemak and laksa varieties unique to the island. But of all the uses of coconut palms and coconuts, however, it’s the amazing by-product of Virgin Coconut Oil that personally fascinates me the most.

Little coconut fun fact: The word coconut (kelapa) can be used to reference the entire poconut Palm tree. The English word is derived from the 16th-century Portuguese and Spanish word ‘cocos’, which means grinning face. The grinning face inspiration came from the three small indentations on the coconut shell that resemble facial features (at least the eyes, nose and mouth area).

To the Portuguese and Spanish of old, the coconut shell resembled a ghostly creature from Latin folklore known as coco, a sort of “ghost monster” figure used to scare children. The term coco was first recorded in 1555, but of course, coconuts themselves have been around far longer than that. Fossil evidence found in Australia and India shows that coconuts date back as far as 55 million years!

Serai/ Lemongrass/ Cymbopogon citratus

Tall tufts of grass are a common sight along kampung roads, but serai (lemongrass) stands out with its distinct citrusy aroma. It’s also a staple in nearly every local household, used both in cooking and as a mosquito deterrent. Personally, I haven’t found it very effective at repelling mosquitoes, but when it comes to flavoring food and beverages, I’m a huge fan of lemongrass.

Serai is often boiled with lime leaves and ginger to make Teh Serai, an herbal tea used to aid digestion and detox the body. It’s also a key ingredient in local dishes like Rendang, Tom Yum, and the absolutely delicious Ayam Percik, a serai-marinated chicken, basted with coconut milk and spices, then slowly grilled over a fire. So good! You’ll taste the lemongrass right away. Once you’ve had a proper introduction, you’ll forever recognize its scent and flavor.

Daun Pandan/ Screwpine/ Pandanus amaryllifolius

My first encounter with pandan wasn’t in a Langkawi kampung, but in the backseat of a taxi in Singapore. Bundled up giftwrap-style beneath the rear window, the long, green leaves gave off a scent that was completely foreign to me, yet familiar: floral and fresh bread-like. It was part air freshener, part talisman, and entirely captivating. That moment left a lasting impression, and to this day, pandan remains one of my favorite aromas. I was also pretty excited to learn that pandan repels household insects like cockroaches.

In Langkawi local cuisine, pandan leaves are often tied into neat knots and dropped into boiling water, coconut milk, or glutinous rice to release their unique aroma and flavor. There’s also air pandan, a green extract made by blending the leaves with water, used as a natural flavor and dye in cakes, jellies, and kuih.

But pandan’s appeal extends beyond the kitchen. It’s not uncommon to see it tucked into drawers, closets, or cars as a natural air freshener. Some believe it repels cockroaches, and others say it wards off bad juju. Whether for scent, superstition, or both, pandan has long earned its place as a humble kampung hero.

There are actually two common types of pandan you’ll come across during a Langkawi kampung walk: pandan wangi and pandan biasa. Pandan wangi is the more fragrant of the two, and its leaves are softer. Pandan biasa has slightly serrated edges and stiffer leaves.

Pokok Pisang/ Banana/ Musa acuminata

Pokok pisang (banana plants) are commonplace along kampung roads. So, if you’ve never seen bananas growing on a tree before, you’re in for a real treat. But take a closer look at the accompanying flower and you’ll see exactly where banana babies come from. Beneath each petal, tiny finger-looking protrusions emerge that become the actual banana fruit!

I grew up only ever seeing bananas at western grocery stores with a Chiquita label slapped on them. That’s why banana plants still fascinate me today. And of course, those bananas of my childhood don’t come anywhere close to the taste of fresh Malaysian bananas, of which there are over 20 different varieties.

Another cool thing is that the entire pokok pisang plant is useful. In addition to the fruit itself, the leaves are often used by locals as food wrappers or plates, the center of the trunk can be eaten as a vegetable, and even parts of the flower are edible. Once you’ve met a banana plant in person, you’ll never look at the supermarket bananas the same way again.

Pokok Kekabu/ Kapok Tree/ Ceiba pentandra

Meet pokok kekabu (AKA the kapok tree). Kapok trees are Malaysia’s version of the cotton plant, only on a much grander scale. Instead of tiny puffballs, they produce large, fuzzy pods that look a bit like corn cobs. Inside, you’ll find soft, silky fibers that have been used for generations to stuff pillows, bolsters, and mattresses.

Back in the day, kapok was everywhere in traditional bedding. Even now, its fibers are prized by locals who swear they make the perfect pillow filling. If you’re wandering through a Langkawi night market, keep an eye out, because there are still a few local pillow makers around, and you might just spot a stack of handmade kapok pillows tucked among the wares and local foods.

Kapok “cotton” is a fascinating material because it’s lightweight, resistant to pests, and renewable, making it a sustainable choice long before “eco-friendly” was a buzzword.

And here’s a little wow factor for you: Kapok trees are also massive and can grow up to 240 feet. Its story stretches into medicine and industry too, but that’s a deep dive for another day (or a quick scroll through Wikipedia if you’re curious).

Selasih Thai/ Thai Basil/ Ocimum basilicum var. thyrsiflora

Although at a glance it looks very much like several similar-looking roadside shrubs, the smell of thai basil leaves is a dead giveaway. Called selasih thai in Malay, thai basil is well-known for its bold aroma and distinctive flavor. The pointed, dark green leaves and deep purple stems make it easier to spot in a garden or at local markets, but it looks nothing like sweet basil plants.

Compared to sweet basil, thai basil has a spicier, anise-like bite with subtle clove notes, which is perfect for flavoring hot broths, stir-fries, and curries. It’s not usually eaten raw.

This sun-loving perennial thrives in Langkawi’s humid climate and is often planted in pots or tucked along garden borders for easy picking. I’ve also found them growing wild on the side of a few roads. Thai Basil is traditionally valued for its digestive and anti-inflammatory properties, with a long-standing place in home remedies and herbal teas.

Kucing Galak/ Indian Copperleaf/ Acalypha indica

This nondescript little plant is something I haven’t been able to find on my own (yet). One of my neighbors introduced it to me while I was out walking and I find it very intriguing. The mysterious kucing galak, whose Malay name translates to “excited cat,” is a wild herb famous for its roots, which send cats into a playful bliss similar to catnip. It grows along roadsides and in fields, but it blends very well with surrounding greenery, so it may be a challenge to spot.

In traditional remedies, its leaves are brewed, crushed, or applied as a paste to ease skin rashes, stomach troubles, and other ailments. This annual herb has a long history of medicinal use across South and Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. It’s been used as a purgative, emetic, respiratory aid, and treatment for skin infections, and in some regions, its leaves are also cooked as a vegetable, such as in Kuppaimeni Poriyal (Indian Nettle Stir-Fry).

Pokok Tebu/ Sugar Cane/ Saccharum officinarum

Easy to spot with its segmented stalks and grassy leaves, pokok tebu (sugar cane) is both a sweet treat and a natural medicine. This tall, bamboo-like plant grows in rows along kampung roads, and in people’s yards as part of their landscaping. In kampung households, it’s sometimes chewed raw or used in folk remedies to cool the body and soothe sore throats.

Its juice, known locally as air tebu, is a must-try, especially chilled on a hot Langkawi afternoon. Locals love pressing the juicy stalks, especially during fasting months, for a naturally sugary drink. If you see tall, green stalks that look like a cross between corn and bamboo, chances are you’ve stumbled on a homegrown sugar cane patch.

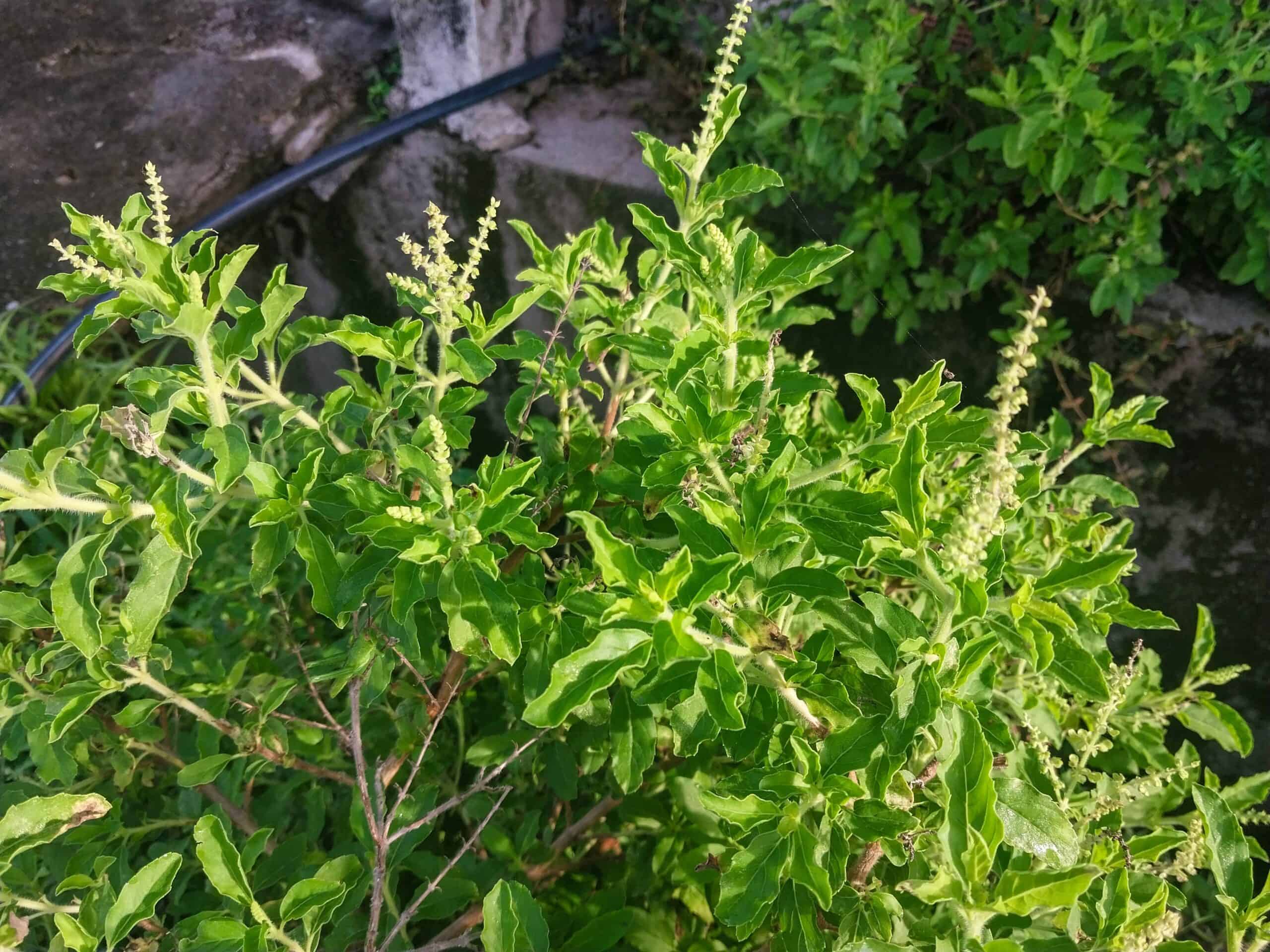

Misai Kucing/ Cat’s Whiskers/ Orthosiphon stamineus

One of my favorite little kampung plants, cat’s whiskers is named for its flower’s resemblance to a cat’s whiskers. But unless it’s actually flowering, it can sometimes be tricky for newcomers to spot.

With long, elegant stamens that look like feline whiskers, this herb is as ornamental as it is medicinal. Usually grown in herbal gardens or around healer homes, its leaves are harvested and brewed into tea for kidney health and urinary issues. Bonus: its flowers attract butterflies, making it a kampung favorite for pollinators.

Historically, kampung healers passed down recipes for brewing the leaves from generation to generation, and in some areas, growing misai kucing in the garden was believed to help protect homes from illness by keeping the plant close at hand. Long before commercial herbal teas, locals were already drying the leaves for daily use, making it one of the region’s earliest herbal infusions, locally known as air herba or maajun in Malay.

Buah Gajus/ Cashew Fruit/ Anacardium occidentale

As a seasonal fruit tree, you’re most likely to recognize it in the early months of the year, and sometimes again in September or October. A near twin to Malaysia’s buah jambu air (water or rose apple), buah gajus (cashew fruit) trees belong to the Anacardium family, which also includes mango trees and poison ivy. To me, the water apple and cashew “fruit” look very similar, yet Google says they aren’t actually related.

The telltale sign for newbies is that the cashew fruit has its nut growing on the outside. The cashew fruit is juicy but not commonly eaten due to its strong flavor and astringency. The nut itself is encased in a toxic shell containing urushiol (yes, the same irritant in poison ivy), which is why you don’t see raw cashews sold at the market. These nuts are first steamed to neutralize the toxin, then roasted before they’re ready to eat.

Since these trees are seasonal, finding one heavy with cashew fruits and nuts is a special treat in Langkawi. But if you spot one, look but don’t touch. And definitely don’t try cracking a nut yourself, especially without gloves.

Buah Jambu Air/ Water Apple/ Syzygium aqueum (Burm.f.) Alston

Despite the name, water apple (also called rose apple) are not closely related to apples at all, but rather to guavas and cloves. However, they do taste a lot like apples, and their texture is also similar to their English namesake. Looks-wise, they resemble the above-mentioned bell-shaped buah gajus (minus its cashew nut appendage).

The leaves and flowers of the jambu air have a variety of traditional uses among kampung folks. In addition to being a tasty fruit, the leaves are used for minor skin issues, and the flowers are sometimes used for fevers. The tree’s strong wood is often used as charcoal. Rose apples typically bear fruit toward the end of the dry season, but some trees can fruit twice a year.

The fruit itself is crisp and mildly sweet, often eaten straight off the tree or served with chili salt. Because it bruises easily, rose apples are not readily found in supermarkets and are mostly enjoyed fresh and local.

Native to Southeast Asia, this tree also has cultural significance across Asia, where it’s used in shrine offerings and decorative carvings. Its glossy leaves and delicate flowers make it a favorite ornamental plant that draws pollinators, while its resilience in tropical climates has made it a staple of backyard gardens and rural landscapes for generations.

Kuku Garuda/ Garuda Claw Fern/ Polyscias filicifolia

This striking little bush gets its name from its finger-like leaves that resemble the claws of Garuda, the mythical bird starring in many Southeast Asian folk stories. It’s a woody shrub that many locals have added to their own landscaping efforts, mostly for decorative purposes, but the garuda claw fern also has many uses beyond garden beautification.

Locals have been known to harvest the younger leaves for medicinal and culinary purposes. In addition to the leaves being eaten raw as an ulam (traditional Malaysian salad green), the leaves and roots are sometimes boiled into herbal concoctions for joint health, detoxification, and postpartum care. It’s also used in herbal baths and mashed into a paste as a topical application for skin irritations, rheumatism or to stop bleeding from minor wounds.

Kuku garuda is usually cultivated and purchased, not foraged from the wild. However, it grows easily from cuttings, so it can easily be passed around through the kampungs.

Buah Pinang/ Areca Nuts (AKA Betel Nut)/ Areca catechu

Buah pinang (also known as areca nuts & betel nuts) is a star ingredient in a traditional practice called ‘Sireh chewing’. In this custom, the sliced or chopped areca nut is wrapped in betel leaves, mixed with lime paste, and sometimes spices. It is chewed slowly and eventually spat out once it loses its flavor. The reddish spit is caused by a chemical reaction between the nut, lime, and saliva, and long-term consistent use can stain teeth.

Betel leaves, by the way, are from a different plant altogether. Buah pinang actually comes from the areca palm! The betel plant (daun sireh) is a leafy vine. (The misnomer originated from early European explorers who were new to the botanical wonders of Malaysia and beyond).

Despite its reputation as a ‘recreational’ stimulant, many believe buah pinang aids in digestion and post-meal relaxation; akin to coffee and a cigarette. So, it still remains a part of local culture for many communities.

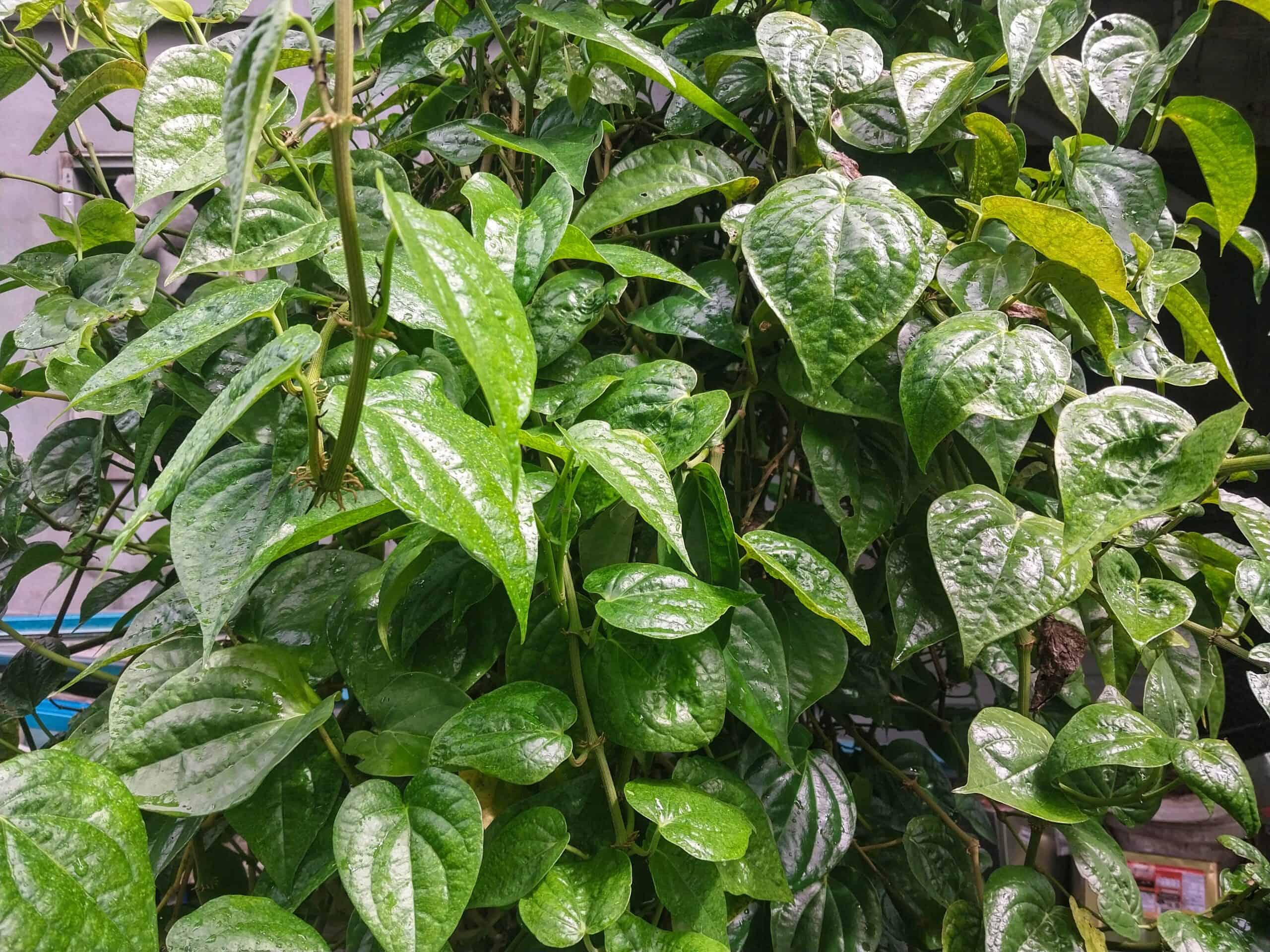

Daun Sireh/ Betel Leaf/ Piper betle

Next up is daun sireh, the infamous betel leaf. Best known in Malaysia as the leafy partner to areca nut (pinang) and a smear of lime paste in the traditional custom of Sireh Pinang. The leaf itself is edible but it’s not a big player in local Langkawi cuisine. Betel leaves do appear elsewhere in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand and Vietnam, where they’re used to wrap meats, herbs, and spices.

Traditional medicine is where daun sireh really stands out. The leaf has a long-standing reputation as a natural antiseptic and anti-inflammatory remedy. It’s also a staple in mandi herba (herbal baths) for postpartum care, and has been used for generations as a mouthwash, wound dressing, and treatment for rashes or infections.

However, chewing daun sireh with areca nut or tobacco on a regular basis carries well-documented health risks. The mixture, known as betel quid, stains teeth and creates the distinctive red spit caused by a reaction between the nut and lime. Early European explorers, struck by this colorful practice and its mild stimulant effect, labeled it a narcotic. That mischaracterization persisted for centuries even though it’s more comparable to coffee and cigarettes than to any narcotic drugs.

Pokok Mengkudu/ Noni (Cheese Fruit)/ Morinda citrifolia

Pokok mengkudu, or noni, is a knobby, pale-green fruit with a strong, distinctive scent. It’s a familiar sight in Langkawi, with the spindly- branched trees often growing wild along the roadsides.

Traditionally, the fruit is left to ferment in glass jars, and the resulting juice is taken as a tonic for energy, blood pressure, and overall wellness. The taste isn’t for everyone, but it remains a trusted remedy in local folk medicine, with recipes and practices passed down through generations.

Hardy and very easy to grow, mengkudu trees thrive in the island’s tropical conditions with little care. While not a staple in everyday cuisine, the fruit is valued for its medicinal role and is still part of many home-based health routines today.

Pokok Ketapang/ Indian Almond Tree/ Terminalia catappa

Ketapang trees are a common sight along Langkawi’s seaside kampung roads and beaches, where their wide branches provide much-needed shade. The large, leathery leaves shift from green to yellow to red before dropping, creating a brief splash of color that almost feels like autumn. These trees handle sandy, salty soil well, which is why they’re often planted along beaches and coastal roads.

Traditionally, ketapang had many uses in coastal communities like Langkawi. Its lightweight wood was occasionally used for canoe building, house posts, and simple furniture. The bark and leaves were part of village medicine, and fishing communities often soaked the leaves in water to treat wounds; a practice I’ve actually seen firsthand from a local fisherman. The tree’s fruit contains small almond-like seeds that are edible but more popular with local squirrels than people.

Today, ketapang leaves are better known in fish-keeping. Dried leaves are used in aquariums to lower pH levels and create blackwater conditions, mimicking the natural habitats of many Southeast Asian fish species, and they’re especially popular among betta keepers.

Ulam Raja/ King’s Salad/ Cosmos caudatus

Last but not least is ulam raja, the humble little plant that inspired this massive blog post. Known as king’s salad, this green is a staple in many traditional Malay meals and is a must-have at Langkawi’s famous nasi campur buffets. It’s often served alongside other fresh vegetables, such as daun selom (water celery) and timun (cucumber slices).

Originally from Latin America and introduced to Southeast Asia by the Spaniards, ulam raja has found a permanent home in Malaysia, where it thrives in kampung gardens and graces dinner tables across the country. Its young, feathery leaves have a refreshing citrusy bite that pairs beautifully with steamed rice and a variety of flavorful mains.

This hardy, sun-loving annual flourishes in Langkawi’s tropical climate and is valued as much for its health benefits as its flavor. Rich in antioxidants, it has long been used in traditional practices to promote blood circulation and overall wellness. The tender young leaves are best picked in the morning, when they’re at their freshest.

In flowering season, ulam raja produces delicate lavender-pink blooms that brighten gardens and roadsides. Despite its unassuming appearance, this so-called “weed” is one of the most recognizable and beloved herbs in Malay cooking.

Pokok, Daun, Buah, Bunga: The Kampung Plant Code

In kampung life, the way plants are named in Malay is wonderfully down-to-earth. If you hear someone say pokok, they’re talking about the whole plant or tree, like pokok pisang, the banana plant. When it’s the leaves that matter, the name switches to daun, as in daun pandan used for cooking. If the fruit is the star, you’ll hear buah, such as buah mangga for mangoes. And when the flower is the focus, it becomes bunga, like bunga kantan, the fragrant torch ginger. These simple prefixes, pokok, daun, buah, and bunga, make it immediately clear which part of the plant people are really talking about. Clever, no?

Final Thoughts: A Living Encyclopedia at Your Feet

Langkawi’s kampungs are scenic, living libraries of traditional local knowledge. Langkawi village walks can become a one-of-a-kind cultural experience if you keep your eyes open. Of course, there are many more interesting kampung flora than what I’ve listed, but I’ll leave them for you to discover on your own.

And as you stroll (or speed walk) the back kampung roads of Langkawi, just remember that many of these plants and trees have been part of local life for generations. So, if you’re planning a trip to Langkawi, be sure to take a village walk, because it’s where island life truly blooms.

Pro tips for Village Walks in Langkawi

PLEASE Do NOT forage any of these plants for food or medicinal purposes without a local expert to ‘guide’ you. Some of these plants require special preparations before being ingested as food or used as medicine. I’m serious.

Showing interest in a plant is one thing, removing the plant or plucking fruit from a tree is a different story. Don’t. If offered, sure, but never assume ‘it’s free’ if there isn’t a house nearby.

Dressing more modestly will always be appreciated when walking through more traditional local Malay villages. It’s respectful (regardless of what ‘others may tell you’). Trust me on this one.

Taking Photos: Langkawi village walks can be a fabulous Instagram opportunity, but please be mindful of taking identifiable photos of people or their houses without permission. And this is especially true with taking photos of children. If no adults are around to give permission, don’t do it. It’s invasive and you are on their turf (not at a tourist venue).

Curious about these local plants, but just don’t feel like walking? You can head to Mardi Agro Technology Park or Muzium Laman Padi, to check out their flora collections. Not quite the same as an invigorating kampung walkabout, but you’ll definitely learn something new.

Hi. It would be much appreciated if I could have some pointers on any easy kampung walks please? I’d love to do some more ‘off piste’ exploring and see more of the true natural Langkawi. We will have a car so any part of the island would be fine, tho we are staying in the northern part of the island, so near the Datai or Tanjung Rhu would be really helpful. Whenever we come to Langkawi I’ve always been unsure about driving much away from the main roads since there is no detailed road map available.

Thanks.

Across from the Tanjung Rhu Beach sign and parking lot… there are a few mini roads that lead into the padi field. Truly, just start walking and follow the side roads. Alternatively is any area near the ‘pink bridge’ in Kuala Teriang/ Padang Matsirat. Walk the main highway north until you come to a side street and then follow them. The bike tour with Dev’s Adventure actually covers much of the Kuala Teriang/ Padang Matsirat kampung walks so you can get a better feel for the area. This is generally where I walk nearly every day. It took me a while to find my own ‘loup’ so I wouldn’t get lost, but I generally just stick to the small paved roads. Don’t follow any paths into wooded areas though because you could just end up in someone’s back yard. :D